Closing the action gap: How humanitarian and climate adaptation actors can support resilience in conflict zones

As part of the World Leaders’ Summit at COP26, international leaders and experts discussed the causes of this action gap and key measures to increase investment in climate change adaptation

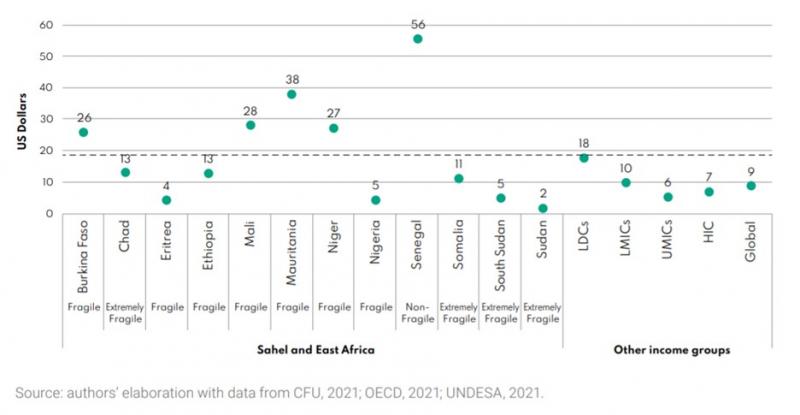

Farmers and pastoralists in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa are highly vulnerable to compound climate change and conflict risks: climate change exacerbates the drivers of conflict, including resource scarcity, and conflict reduces people’s and institutions’ ability to adapt to climate change. However, as SPARC research has shown, despite this vulnerability, most fragile and conflict-affected countries in the Sahel and Horn of Africa region receive less climate change adaptation funding than other Least developed countries (LDCs).

During a hybrid high-level event organised by Supporting Pastoralism and Agriculture in Recurrent and Protracted Crises (SPARC) as part of the World Leaders’ Summit on the first day of COP26, international leaders and experts discussed the causes of this action gap and proposed key measures to increase investment in climate change adaptation in fragile and conflict-affected countries. They called for closer cooperation between humanitarian actors, who provide crucial support to address immediate needs but tend not to focus on long-term resilience building, and the adaptation community, which specialises in long-term planning but is not set up to work in conflict-affected, unstable environments.

In his opening remarks, Alambedji Abba Issa, Minister of Agriculture of Niger, sketched the compound risks Niger is facing. The impacts of climate change are already contributing to reduced agricultural production and increased poverty in the absence of stronger agricultural value chains and adaptive agriculture. These may interact with conflict dynamics and enhanced the double vulnerabilities people face from actors, such as armed groups that destroy livelihoods, and climate pressures on land and water resources. An ODI report highlighted that climate change is another pressure layer upon conflict stressors and livelihood shifts already underway in Niger, but not causing them. Thus, there is a need to address underlying vulnerabilities, as stressed by Mr Issa. The solutions needed to address climate impacts must also reduce the risk of conflict such as, corridors and water points to allow pastoralists to move more freely, intensified farming to reduce conflict over land, and sustainable provision of water, food and cooking facilities to people displaced by terrorism.

Connecting the humanitarian and climate adaptation communities

A holistic, coordinated approach to humanitarian relief and climate change adaptation has great potential across the Sahel region and beyond. As Soukeyna Kane of the World Bank observed, though climate change and conflict risks compound each other, “conversely, conflict prevention and addressing the root cause of fragility can serve as an essential enabler of climate adaptation […] while effective adaptation in FCV [fragile, conflict-affected and vulnerable settings] settings can serve to strengthen resilience, improve livelihood opportunities, and reduce drivers of political conflict.”

Though they address closely interconnected and often overlapping issues, the humanitarian and climate adaptation communities have different mandates, funding mechanisms and terminologies, and their work is guided by different international agreements. For example, as ODI Chief Executive Sara Pantuliano remarked during the event, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction does not mention conflict or fragility. However, people do not face threats in isolation, and should not receive support for single threats- whether these are a climate shock like a drought or an incident of violent conflict- in isolation, either. Instead, humanitarian and climate change adaptation actors must consider the entire political-economic context when designing interventions, to enhance effectiveness and avoid exacerbating risks or creating maladaptation.

We need to talk about risk

A major barrier to channelling more adaptation funding into fragile and conflict-affected countries is the risk of making long-term investments in such unstable settings. Much of climate finance is provided as loans or made contingent upon the provision of co-financing or private sector involvement, which makes it inappropriate for conflict situations. In many cases, governments must apply for climate finance themselves, but governments in conflict-affected countries often lack the capacity and the baseline data to meet onerous application requirements.

As a result of the (real or perceived) risks attached to working in fragile countries, humanitarian interventions in the Sahel region often have primarily short-term goals, and activities to support the government in the long term, such as capacity and institution building, are not undertaken. When programmes do include an element of capacity building, this is often left to external partners and not always well-structured, which undermines country ownership.

Building capacity and institutions

However, Ahmed Yusuf Ahmed of the Federal Government of Somalia argued that exactly this type capacity building and technology transfer support had been key in empowering his government to respond to the climate change challenges it faces. He said that such support “really enhanced the Somalian ownership of its NAP [National Adaptation Plan] and NDC [Nationally Determined Contribution] and move forward the effective implementation of mechanisms as well as the implementation of national adaptation plan.”

Long-term capacity and institution building is also important because, as Soukeyna Kane highlighted, weak government institutions tend to further compound stresses: “they find it very challenging to mount a strong response to crises, cushion the impact on the most vulnerable population as well as invest in long term conflict prevention and climate adaptation,” and risk becoming “trapped in a vicious circle of instability if they fail to adapt to the effects of climate change.”

Finding a joint way forward

How can the humanitarian and climate adaptation communities move forward together? The panellists discussed several promising approaches to boosting climate adaptation in fragile and conflict-affected settings.

Nick Dyer, UK Special Envoy for Famine Prevention and Humanitarian Affairs, discussed the promise of emerging anticipatory action mechanisms, which put in place pre-agreed and pre-arranged financing that can be released when certain shocks happen, or are projected to happen. He noted that such mechanisms can protect hard-won development gains, and that though many are currently funded by the humanitarian community, they could just as well be funded by the adaptation community. Both communities will need to be involved to take such initiatives to scale, as neither has the capacity or experience to do so on its own.

Mikko Ollikainen of the Adaptation Fund argued that the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) should recognise fragile states as particularly vulnerable, to allow them easier access to climate finance: “There is a need to streamline the access modalities for climate finance in fragile countries. We have done that with small island developing states and least developed countries, but so far there hasn't been adequate attention paid to fragile situations.”

The speakers also stressed the need for tailored, context-appropriate and co-created interventions. Soukeyna Kane called for “conflict-sensitive adaptation, which avoids exacerbating factors that contribute to the conflict, and actively promotes factors that build peace and improve livelihood opportunities.” Nick Dyer said the goal should be “to build on the solutions and the ideas that actually are held in communities and individuals who on a day-to-day basis, see, suffer and respond to climate change – to create space to empower those people to co-create solutions and to build knowledge and systems.”

Find out more about SPARC at COP26, and watch SPARC and ODI join the debate at the World Leaders’ Summit event here