Why climate information matters for pastoralists

Reliable weather and climate information services (WCIS) are vital for pastoralists' resilience in drylands. Here we explore what we know about WCIS for pastoralists and what needs to change.

If we want to reduce the risks of climate change, we need to know what’s coming—both in the long term and in the day-to-day weather. When we make decisions based on robust information, we reduce the risk of negative consequences of a changing climate.

The good news is that the availability and quality of climate data has improved dramatically in recent years. The challenge is that data only becomes useful when it’s tailored to the decisions people need to make. A water manager deciding how much water to release from a dam needs vastly different information from a farmer planning which crop varieties to plant. This is where Weather and Climate Information Services (WCIS) come in.

WCIS is all about turning climate data into actionable climate information—and making sure that information reaches the people who need it in a timely manner and through channels that are suitable for them. Crop agriculture has received plenty of attention in this space, but pastoralism has received less attention.

To address this, a team from SPARC recently undertook a scoping review set out to explore what we know about WCIS for pastoralists. This research was a continuation of work SPARC has undertaken with partners Mercy Corps and the Jameel Observatory Food Security Early Action on ways to enhance WCIS to support dryland adaptation and resilience. Our evidence and engagement have included:

- Hosting events with government, private sector, civil society and pastoralists to better understand how to improve access to reliable, timely WCIS.

- Holding a workshop with local actors and stakeholders in Wajir, Kenya, to explore ways to overcome barriers to generating and sharing WCIS.

- Convening a dialogue where policymakers, pastoralists and entrepreneurs in Wajir - who are already using WCIS in new ways to support decision making - shared key insights from their experiences.

- Providing steps government can take to scale effective WCIS in drylands.

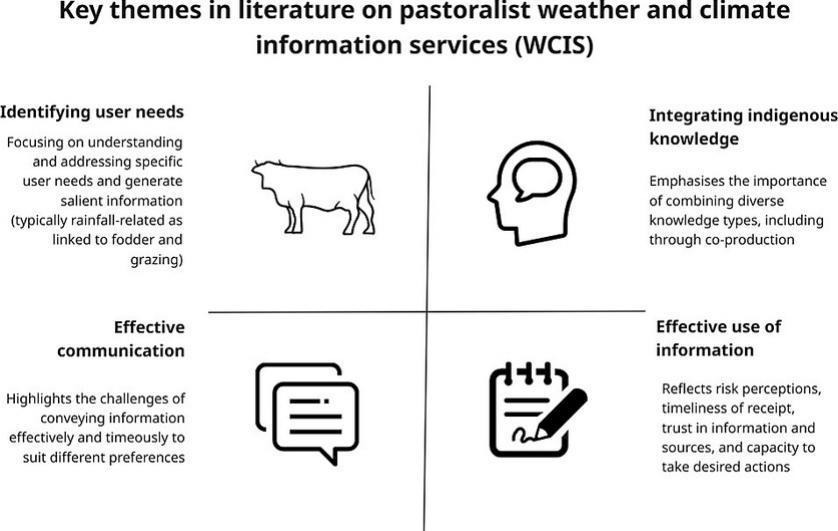

What the review found about pastoralist WCIS

Our recent review looked at 51 documents from journals and grey literature, so the evidence base is relatively small. Most of the research—over three-quarters—focuses on Africa. But there are examples from Europe, Asia, Australasia, and the Americas too. Several of our findings stood out:

- Role of indigenous knowledge

One standout finding was the strong role of indigenous knowledge. Unlike crop farming, pastoralism often relies on traditional forecasting methods. For example, observing animal behaviour, reading atmospheric patterns, studying the stars—or even examining animal intestines—to predict rainfall and seasonal conditions. These practices remain deeply embedded and trusted.

- How pastoralists get information

Getting timely, relevant information to pastoralists is tricky—especially because they are mobile, and often in areas of poor connectivity. The review found that WCIS reaches pastoralists through radio, word of mouth (via extension agents or other herders), mobile phones, and sometimes email. But access isn’t equal. Women, for instance, are less likely to own radios or phones or interact with extension agents, which creates barriers to them receiving information.

- Barriers to use

Even when information gets through, being able to use it is another story. WCIS is often shared in national languages, which not everyone speaks or reads. Forecasts can be packed with technical jargon that is hard to understand. And the content is not always tailored to pastoralists’ needs. For example, it may cover areas that are too broad or not give specific enough information about when rain is likely for it to be useful.

Then there is the issue of trust. Scientific forecasts are sometimes seen as inaccurate, and indigenous knowledge often feels more reliable. These barriers—language, complexity, relevance, and trust—limit how effectively pastoralists can use WCIS. These barriers resonate also with literature in crop agriculture and other sectors.

Looking ahead

Pastoralists’ mobility and their reliance on rangelands for their livestock means that pastoralists’ lives are very affected by changes in weather and climate. Salient, credible, and legitimate WCIS could help them to better manage a changing climate. This is why SPARC published a brief on how weather and climate information can help pastoralists.

The SPARC review highlights a number of avenues to explore to improve accessibility and use. One is indigenous knowledge, which is already commonly used. While some efforts have tried to combine these with scientific forecasts, most stop at using local knowledge to “check” the science. There is huge potential to go further—really blending these systems to create actionable knowledge.

One of the ways to do this is through co-production—bringing information providers and pastoralists together to design services that work for them. Evidence from other sectors shows that co-production can help tackle issues of trust, relevance, and feedback. So far, there is little evidence of co-production in practice for pastoralists. But if this changes, the potential for tailored, targeted WCIS to support the lives and livelihoods of millions of pastoralists in drylands is huge.