An exploration: Influencer-led, social media campaigns in the drylands

Our blog explores what tech firms, agroproducers, private sector actors, government, Non-Governmental Organisations and donors need to know about the impact of social media in the drylands.

What do tech firms, agroproducers and private sector actors, government, Non-Governmental Organisations and donors need to know about the impact of social media in the drylands?

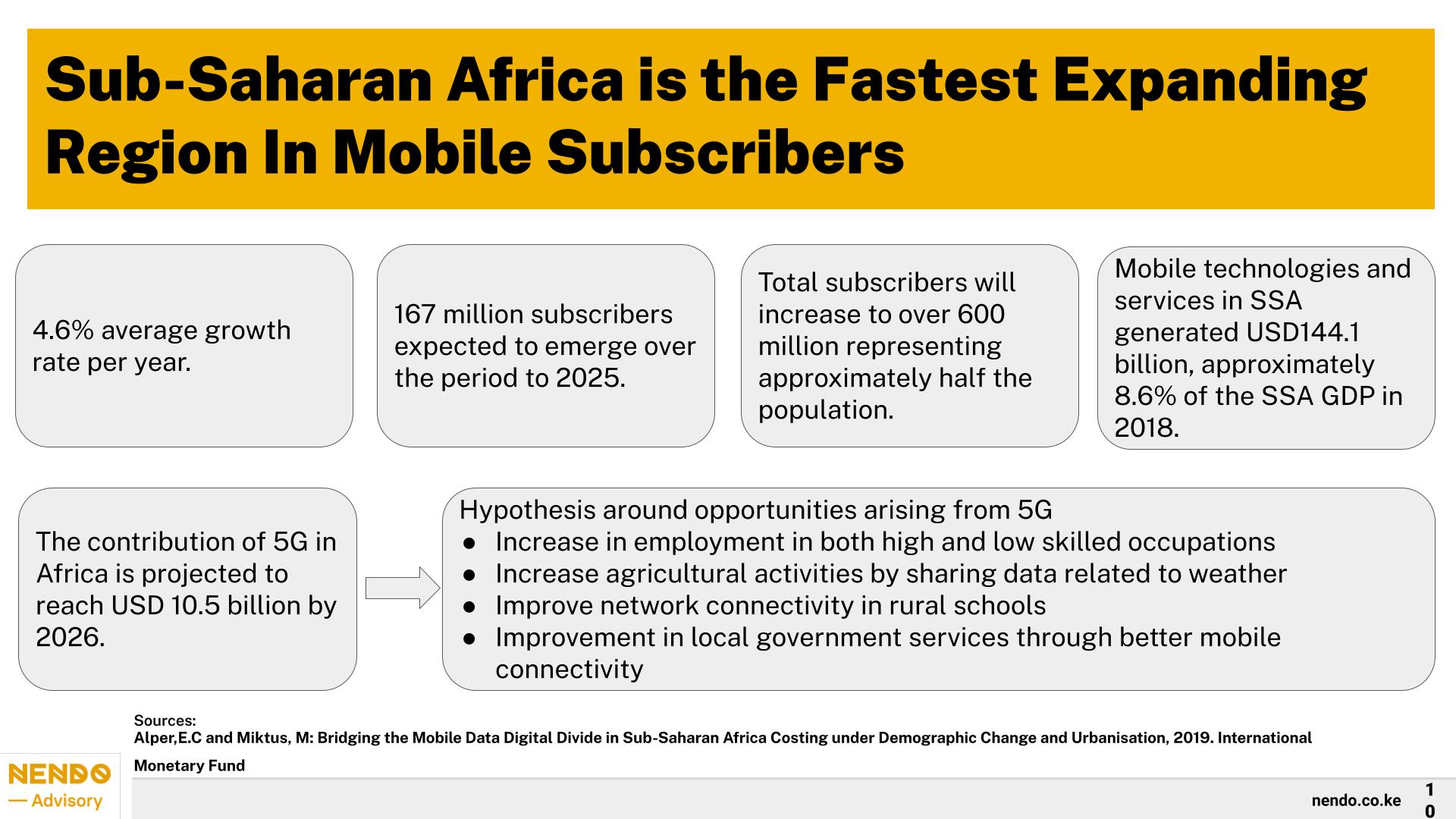

This was one of the questions we asked after SPARC-supported research, carried out by digital consultancy Nendo in 2022, explored how people in the drylands of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Nigeria use mobile phones and social media. The research told an optimistic story about connectivity and digital media use in Africa.

In the face of climate change, conflict and other crises, how drylands communities in Africa access and use social media might not be top-of-mind when it comes to questions to tackle. That is unless you are paying attention to the steadily shifting trends in connectivity on the continent.

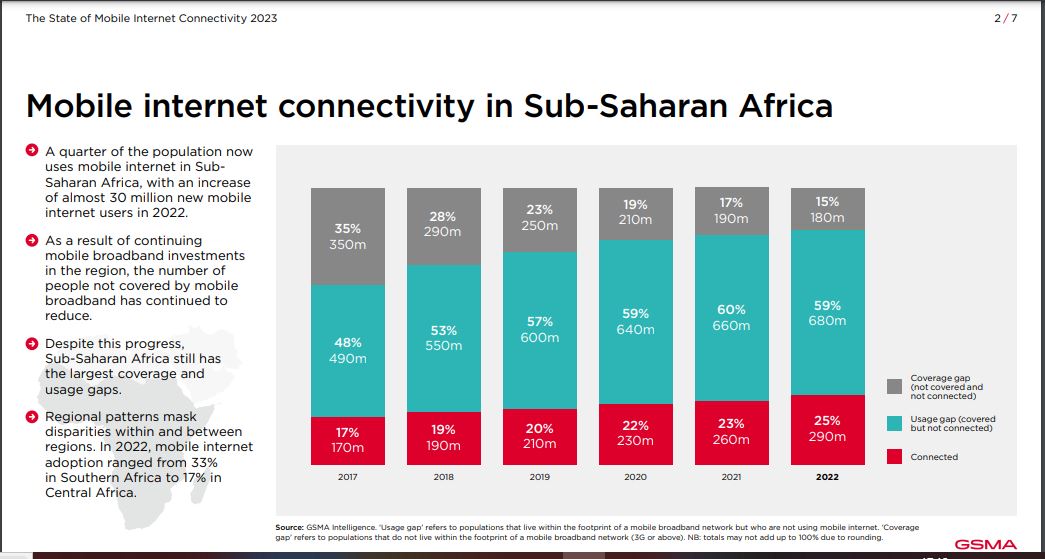

(Source: GSMA State of Mobile Internet Connectivity, 2023)

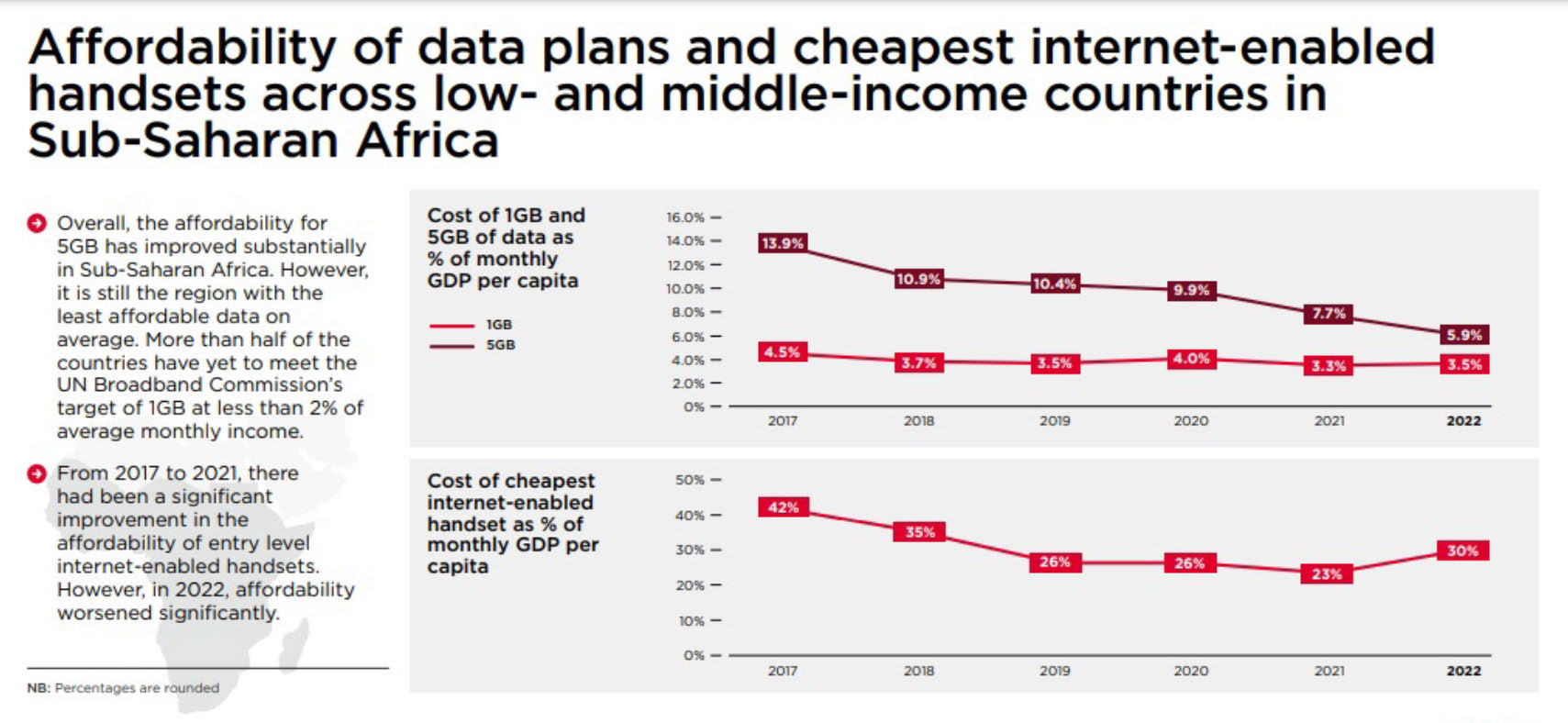

Despite numerous pervasive barriers to network expansion and access to affordable mobile phones and associated networks and services in Africa, barriers that disproportionately affect women, trends are shifting.

(Source: Pan-African perspectives: Hypotheses on digital, social and mobile use in the drylands, SPARC-Wowzi Opportunity profile, Nendo, n.d.)

(Source: GSMA State of Mobile Internet Connectivity, 2023)

Communities and markets, including those in drylands, are leaning into the benefits digital technology and the internet can offer to move products and services, and to gather and disseminate information and data. The train has left the station and there’s no turning back.

SPARC, in partnership with Mercy Corps AgriFin and Dalberg Research, recently hosted a series of webinars to launch joint research on how agroproducers in the drylands of Kenya, Ethiopia and Nigeria use digital information and financial services. The barriers agroproducers in all three countries face to adopt these services were, to a varying degree, mostly the same:

- Poor network coverage (mobile phone and internet);

- Low access to affordable mobile phones;

- Poor digital literacy;

- Lack of awareness of available digital services and their benefits;

- Low levels of trust - suspicion regarding digital platforms and online transactions, (especially financial transactions);

- The gap in mobile phone access for women; and

- Restrictive related policy environments.

And yet opportunities abound in the digital space. Programmes supporting agroproducers could and are harnessing the power of the collective, such as aggregators in agricultural value chains, and community savings groups to improve access to phones and the internet, and consequently to much-needed information and financial services. As with Ethiopia’s Lersha, and Nigeria’s Livestock 247, mobile phones in the hands of extension officers and community animal health workers are powerful tools helping to diagnose, track and treat crop and animal diseases, and supply necessary inputs. They also provide extension and community animal health workers who use these digital platforms with opportunities to carry out dignified work.

Social media

Social media campaigns in particular, if properly deployed, offer a potentially useful opportunity to engage pastoralist, agropastoralist and farming communities, by allowing them to share information, market goods and services, promote sustainable agricultural and pastoralist practices, and improve livelihoods.

So, while acknowledging the wide array of benefits and pitfalls, social media platforms are a force to reckon with.

“Over the past decade, pastoralists have been re/claiming the novelty and utility of mobile phones, and much of the (undelivered) promises of the social media age. Even with the bottlenecks of lagging infrastructure and systemic inequalities in literacy and affordability, targeted investment could unlock a quadrant of opportunities: a) job creation and livelihood diversification; b) social capital and collective action; c) civic participation and ‘social listening’; and d) information-as-a-service, like in market and climate information exchange as well as early warning systems.” explains SPARC researcher Alexis Teyie in an article for The Republic.

Influencer-led social media campaigns

SPARC built on this initial scoping study with Nendo by partnering with digital marketing firm Wowzi to support influencer-led social media campaigns with Savanna Circuit and Kenya Organic Agriculture Network (KOAN).These campaign pilots explored how to harness the power of social media in the drylands, and, specifically, whether influencer-led social media campaigns could be effective drivers for behaviour change and knowledge building among drylands communities.

The Savanna Circuit campaign focussed on creating awareness and driving sales of their solar powered milk chillers - the Maziwa Plus Mini and the Maziwa Plus Mega, and the company’s dairy management system - The MaziwaPlus Dairy Management System (M+DMS).

The target audiences for the campaigns were mainly urban residents with close ties to rural pastoralist communities, and those active in the livestock sector, especially in the drylands. The aim was to introduce the chillers and dairy management system to livestock owners and dairy farmers looking for solutions to milk loss and wastage challenges, while offering flexible options to buy, rent, lease or finance the equipment.

The campaign activities with KOAN gave momentum to the Farmer Influencer Training programme the network had begun with Wowzi. The first phase of the campaign offered farmers training to become ‘farmfluencers’, using their social media platforms to promote organic farming. SPARC’s involvement saw an extension of the campaign by providing an additional focus on the drylands, and our research began to test out ways in which influencer campaigns could be different in these territories.

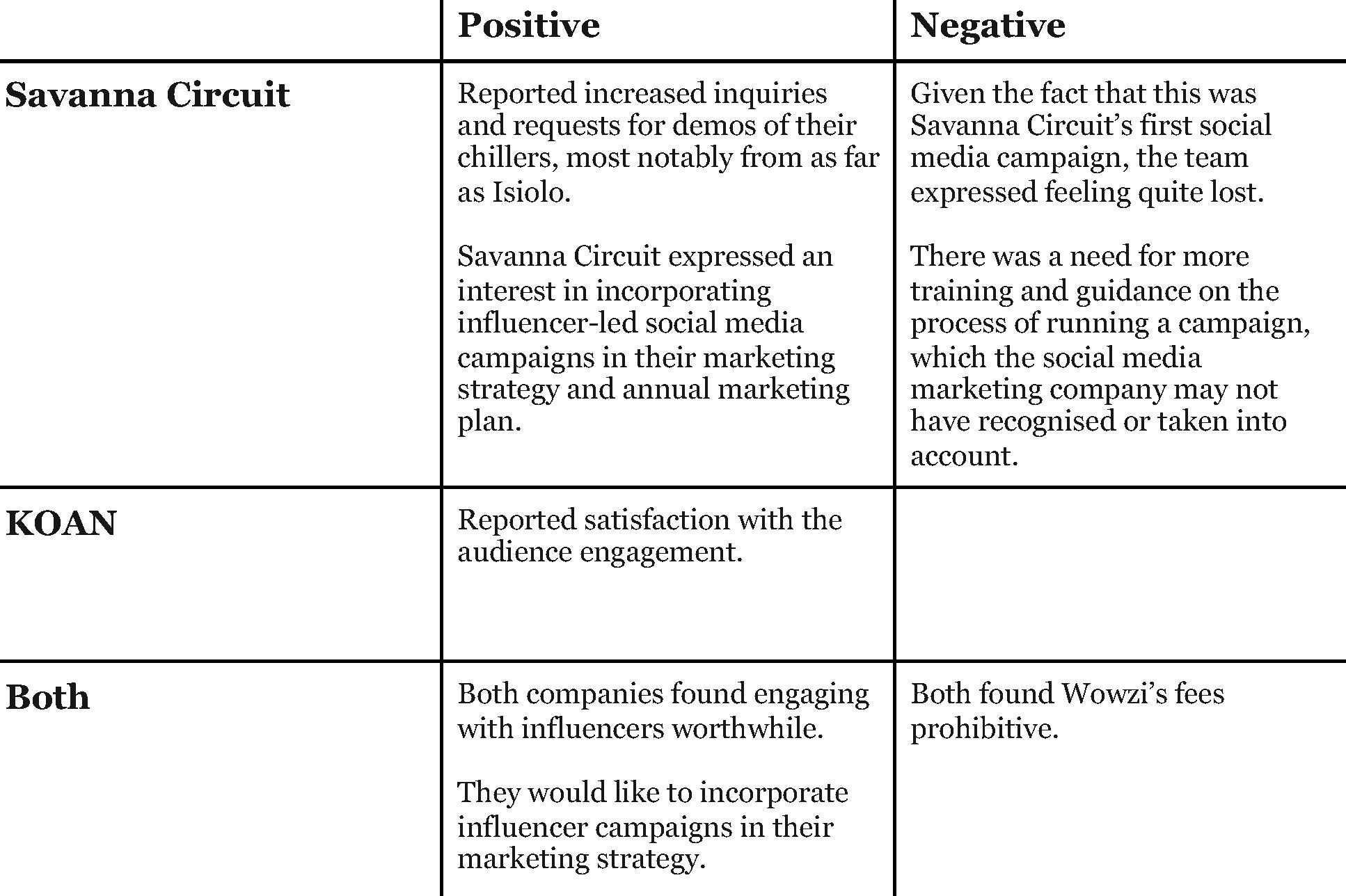

Feedback from Savanna Circuit and KOAN

During the campaign period, KOAN reported experiencing a threefold increase in engagement compared to the previous month. Specifically, there was a 14% growth in Facebook page visits and a remarkable 152% growth in Instagram page visits. Additionally, KOAN reportedly gained 156 new followers on Facebook (14.7% increase) and 45 new followers on Instagram (40.6% increase) during the campaign period.

Although the same data was not available for Savanna Circuit, the team expressed clear benefits of running the campaign.

The cost of running these influencer-led campaigns was prohibitive at about KShs 1.25M each (slightly over US $9,000). Both partners participated because SPARC supported the activity, but said that their marketing budgets could probably not accommodate this spend on a single activity. Clearly there is a need to engage social media marketing companies such as Wowzi, AInfluence and others operating in African markets to explore ways to engage clients working in the drylands affordably and sustainably.

Recommendations for social media campaigns in the drylands

- Continue to work with stakeholders to get the social media marketing service and pricing right for enterprises operating in the drylands;

- Engage with women’s groups, religious organisations, extension officers and aggregators in social media campaigns benefiting drylands communities. This also means reaching them where they are, for instance, community barazas (meeting);

- Engage legacy media to create a hybrid campaign strategy, leveraging the reach of radio, TV, and print outlets to complement influencer-led social media engagement; and

- More stakeholder collaboration is needed to raise awareness about digital technology and social media campaigns, and to boost digital literacy.

Shout out for more data on social media in the drylands

The SPARC-supported influencer-led drylands campaigns led by Wowzi offered an invaluable indication that more such campaigns are needed in the market. Further exploration is warranted - we need to gather more data, acknowledging that influencer-led social media campaigns will, in time, gain greater traction in the drylands. Achieving successful influencer-led social media campaigns means marketing firms like Wowzi must work even more closely with companies to explore:

- Affordability: How to make influencer-led campaigns affordable for businesses offering goods and services in the region. This is factoring in the unique logistical characteristics of the landscape and how to meet costs to navigate them. Options include leveraging the reach of traditional media such as radio, or market days or community barazas (or public meetings) to adopt a multipronged approach to reach audiences more effectively and affordably;

- Culture: What does growing social media use mean for pastoralist ways of life - how communities live, work, interact, communicate, move, and organise themselves? And

- Inclusivity for women: Are the voices of women being heard on social media? How is social media affecting them? Are we disaggregating data to ensure women are in focus? By moving with a clear commitment and strategy on how to reach women in the drylands, taking into consideration the cultural factors that limit or influence women’s phone ownership, and norms which govern where and how to reach them.

We need to ask the right questions as we continue to engage in influencer-led social media campaigns in the drylands. These include:

- Context: In which ways are drylands and pastoralist communities shaping and innovating their use of social media, and curating and shaping the information they receive?

- Socio-cultural impact: How is technology affecting drylands communities’ ways of working, channels of communication and hierarchies of influence?

- Policies and business practices: How is technology impacting business practices in the drylands, and shaping attitudes towards these markets? Could influencer-led social media campaigns play a role in shaping business and livelihoods in Kenya’s arid and semi-arid areas? And

- Psychosocial impact: How is technology affecting the psychosocial wellbeing of drylands communities and their resilience and innovation in the face of climate change and other shocks

- How can digital platforms grow and be strengthened as a space for dignified incomes for pastoralist and drylands communities, especially women?

Questions and more questions, to take us deeper into our exploration of the inevitable world of social media campaigns for the drylands, and the role of social media influencers in sharing information and changing behaviour in the arid and semi-arid lands of Africa.