Dossiers

One more of life’s difficulties: the impacts of Covid-19 on livelihoods in Somalia

How are rural families in Somalia dealing with the impacts of Covid-19? SPARC speaks to farmers, agropastoralists, pastoralists and traders.

Éditeur SPARC

When the Covid-19 pandemic first hit Africa, fears grew about its potential impacts. Lessons from previous health crises, such as the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, had shown the danger of neglecting the damage that epidemics can do to the livelihoods of poor people. Somalia has not been out of crisis for decades because of long-standing conflict coupled with periodic droughts. One of the few famines of the 21st century happened in Somalia in 2011/12 and a massive aid effort in 2017 may have averted another. Apart from international aid, the country’s economy is particularly dependent on remittances and livestock exports – the most profitable market is to Saudi Arabia during the Hajj – both of which were threatened by Covid-19. Unsurprisingly, then, there has been considerable concern for the food security situation in Somalia.

Several organisations have been actively monitoring economic and market data in several African countries. In SPARC, we are complementing this by following the lives of rural families in Somalia, and also South Sudan and Nigeria, as they deal with Covid-19 alongside all the other challenges they face.

In late 2020, SPARC held open-ended face-to-face conversations with 51 farmers, agro-pastoralists, pastoralists and small-business people in three administrative regions, Middle Shabelle, Mudug, and Togdheer (in Somaliland). SPARC will continue to follow the lives of these people and their families over the comings months and years to see how changes are affecting their livelihoods and how they are adapting and coping.

People are taking the threat of Covid-19 seriously

All the people we spoke to were well informed about the disease, including its symptoms, how it is transmitted and how to protect themselves. They had many sources of information, from the local to BBC radio. People were generally taking precautions and voluntarily restricting their own movements. Covid-19 had affected the livelihoods of everyone we talked to in some way, but fears that it would cause a major emergency have not come to pass, so far at least. It has been difficult rather than catastrophic, and for many people Covid-19 was not the main difficulty they had to confront. People’s acute fears about the epidemic were principally about the danger of falling sick and dying, but interviewees and their families were largely unaffected by COVID-19 symptoms to date.

Households have experienced a range of economic impacts

There were few surprises about how Covid-19 affected livelihoods. Remittances from family members abroad fell, as they were affected by economic downturns in wealthier countries. The prices of imported food and some other goods rose, reportedly because import volumes were down as result of reduced international flights. Along the Shebelle River, food prices rose because floods had hit local production. At the same time, livestock prices fell, as predicted. This is partly because the export market was reduced by the cancellation of the Hajj, and because so many people had less money to spend, reducing demand in the local market.

Many livestock keepers responded to the worsening of the terms of trade between livestock (that they sell) and agricultural produce (that they buy for food) by slaughtering more of their own small animals to eat. They also had to sell more animals to maintain their income, which caused some reduction in the size of their herds.

Most of the farmers, agro-pastoralists, pastoralists and small-business people we spoke to had relatives who depended on non-agricultural livelihoods, many of whom lost their incomes because of Covid-19. Teachers also lost their incomes while schools were closed, employment opportunities in construction were curtailed and many different markets were depressed. Even the second hand clothes market was affected because fewer clothes were being imported as a result of international travel restrictions.

Other impacts of Covid-19

People have also been hit both by other indirect impacts of Covid-19 on their livelihoods, as well as facing difficulties in other areas of life. General restrictions on movement in Somalia has limited access to veterinary services. Livestock keepers spoke of the deaths of camels and goats, for instance. Goat mortality is almost certainly from Contagious Caprine Pleuropneumonia (CCCP), for which there is an effective vaccine, but it would be misleading to suggest that without Covid-19, there would have been effective control of CCCP across the country through a complete vaccination programme. Herders had been reporting camel mortality long before the current pandemic restricted veterinary services.

A few of the people we spoke to explained that movement restrictions had curtailed programmes assisting agricultural production, although again, it would be wrong to overestimate the coverage which such programmes were achieving before the pandemic. Restrictions on movement also affected market operations beyond those of livestock. Farmers were finding it harder to buy sufficient agricultural inputs, due to the combination of the increased price of fertiliser and their lower disposable income. It is hard to predict what impact this will have on food production or food security.

When asked about their greatest unhappiness related to Covid-19, most respondents spoke of their worries for their children being out of school and the loss of a communal social and religious life, in particular of prayers.

Meanwhile life continued with its ups and downs

In most places, rangeland conditions were good because of favourable rains and unimpeded mobility for herders. The animals were therefore faring well, and the good rates of reproduction were compensating to a large degree for increased offtake from the herd for slaughter and sales.

Farmers and agro-pastoralists along the Shebelle River (particularly in Balcad) had suffered from floods, which had affected them far more than Covid-19, preventing some from farming altogether and causing local disturbances in the availability of some local food products in market. In some areas losses from animal health problems (e.g. CCPP as mentioned above) were greater than those caused by the increased offtake as a reaction to Covid-19.

So far, people are coping

Overall, most people were either receiving help from other family members or were having to help other family members who hit worse than they were. Most people said that neither they nor anyone in their communities had received any assistance from Government or agencies because of Covid-19. One person reported distributions of face masks and hand sanitiser from the federal government, and one other reported receiving seeds. Others told us that whereas they had previously been receiving assistance before Covid-19, for example for agricultural production, it had stopped because of the pandemic.

People were finding their own ways to cope with the loss of markets. Livestock keepers reduced the number of animals that they had to sell by selling more cow’s milk. Those who had been selling milk in markets adapted to the loss of footfall in local markets generally by making and selling butter (which has longer shelf life than milk) or going door to door to sell milk.

The additional sales of animals was not (yet) unmanageable. Only goats and sheep were being sold (but not of cattle and camels), and the size of the herd reduction was not comparable with the impact of a drought. We would expect herders to be able to recover these lost animals fairly quickly, if the problems do not persist for too long. Where pasture conditions were favourable, people even reported that their herds had increased.

Lessons for aid actors

The impact of public health restrictions, including the closure of schools for several months, is serious. If future waves of the disease are more serious, it may be useful to explore how to help people to find ways to maintain as many activities as possible in safer ways rather than just by restricting which activities are allowed. It will be important to work together with the leaders of different kinds of institutions , for example with Quranic schools, some of which stayed open while other schools were closed, to develop Covid-safe continuity as an alternative to imposing bans that may not always be heeded.

If the impacts of Covid-19 continue, it will be important to support people’s productive capacity at scale. For livestock keepers, supporting veterinary services may be one important form of assistance. Our brief conversations to date are not sufficient to know how best to do this in different places, but there may be issues with the accessibility of veterinary drugs in some places and the need to prioritise investment in animal vaccination campaigns in others.

Although we only spoke to people in rural areas, many reported either receiving help from relatives or having relatives now relying on them. The connections between family members and the interconnectedness of agricultural and non-agricultural livelihoods is not new information. It is, though, an important reminder not to think of families in these communities in relation to only one livelihood type. Achieving diversification through such family interconnectedness is an important way of risk sharing. Although it is a source of resilience, this is because it dilutes vulnerability by spreading risk, rather than by erasing the risk. The other side of the coin is that it exposes more people to the effects of any particular shock.

Confluence of different challenges

The main livelihood concerns faced by farmers and herders in Somalia in the coming seasons will not be specifically focused on Covid-19, but on the confluence of different problems. Covid-19 adds just one more challenge, but each additional difficulty brings some people closer to the point where they cannot cope.

The future development of the pandemic in Somalia is highly uncertain. New strains may prove more infectious, and mass vaccinations are unlikely to be running at scale for some time. So far, the damage to people’s livelihoods has been limited, partly because of largely favourable climatic conditions - except where people were hit by floods. However, if, as predicted in parts of Somalia, conditions deteriorate because of poor rains whilst the Covid-19 stress continues, the combination of stresses could quickly turn a difficult situation into a serious one.

Don't miss SPARC’s analysis of how shocks have affected livestock markets in Somalia and the Horn of Africa, impacting smaller, poorer traders more than wealthier ones, and how the Hajj cancellation in 2020 due to Covid-19 was only one of many disruptions to the sector, read ‘Rapid Assessment of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic’.

Future livelihood monitoring by SPARC

SPARC is currently engaging in a second round of conversations with the same groups of farmers, pastoralists, agropastoralists and small-business people. Because there are currently predictions that the coming rainy season will be below normal, there are fears that the food security situation will deteriorate. We are therefore trying to understand how these communities are looking and planning ahead, to see if we can help identify potential ways of assisting donors, programmes and policy makers to design and implement anticipatory actions in future droughts.

We will be following the lives of these same people at regular intervals throughout the coming months and years. We hope to bring rapid updates about what we are hearing.

This article is part of a three-part SPARC learning project to understand how farmers, herders and those living in conflict-affected areas in South Sudan, Nigeria and Somalia are coping with and adapting to multiple shocks and stressors.

This feature, the first part of the project, highlights research on people’s lives, livelihoods and wellbeing. The second part captures people’s experiences of social cohesion, conflict and conflict mediation, and situates these within broader security contexts gathered from government, research and non-governmental organisation (NGO) reports and media sources. The third piece, coming online later in 2021, will monitor rangeland, livestock and market conditions.

Together, the three pieces will help us to understand how farmers, pastoralists and agro-pastoralists in drylands are making decisions as conditions change with time. The research will also enable us to ground recommendations to donors, NGOs and local and national governments on how to assist these groups more effectively, and support and complement locally led resilience actions.

At SPARC, we want to broaden the range of people we hold these conversations with, both in Somalia/Somaliland and in other countries, and would like to know how to make our conversations and these updates more useful. Organisations interested in collaborating with us to do this can contact: [email protected] or [email protected]

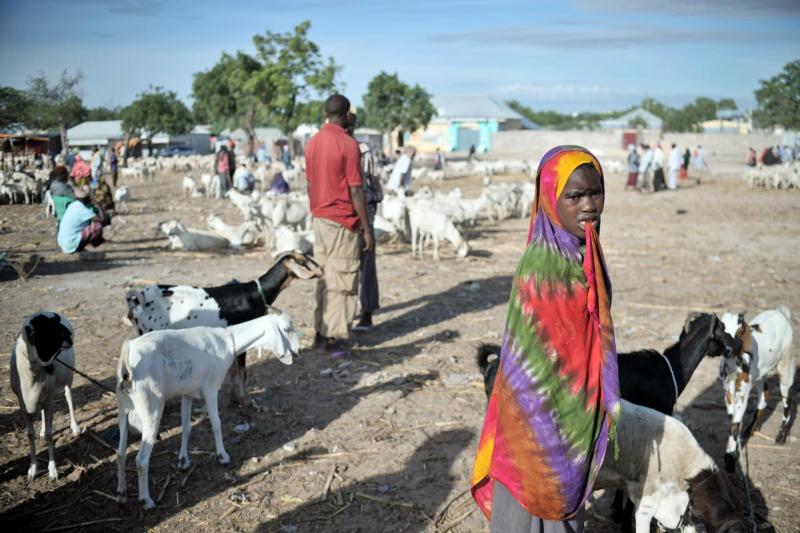

A girl stands watch over a herd of goats at Bakara Animal Market in Mogadishu, Somalia

Credit Image by Tobin Jones / AU-UN IST - CC0 1.0 Universal