Blog

Adaptive, agile research in drylands: Lessons from a survey on participatory governance

Three lessons on how agile collaboration enables rigorous research in tough environments.

Publisher SPARC

As budget cuts mean development actors face growing pressure to deliver results in fragile and climate-affected regions, the demand for rigorous, context-sensitive evidence is rising. Yet conducting high-quality research in such environments remains a major challenge.

In our recent research study on Ward Development Planning (WDP), we worked across five counties (Garissa, Isiolo, Marsabit, Turkana and Wajir) in northern Kenya to understand how a participatory governance intervention shaped local attitudes and behaviours. What made this survey possible was adaptive management: a real-time, collaborative approach to problem-solving. Here we share three key lessons from that experience, showing how agile collaboration enables rigorous research in tough environments.

Tension between survey methods and adaptive management

Survey methods and adaptive management may seem like an unlikely pair. Surveys rely on standardisation across contexts to yield reliable, valid results. In contrast, adaptive management thrives on flexibility and responsiveness to local context.

But our experience with the WDP survey shows how these approaches can be complementary in drylands and other fragile settings. By incorporating real-time, on-the-ground insights, we adapted survey protocols to local realities. This flexibility allowed higher fidelity to the research aims while respecting time, cost, and safety constraints.

Adaptive management in the Ward Development Planning (WDP) survey

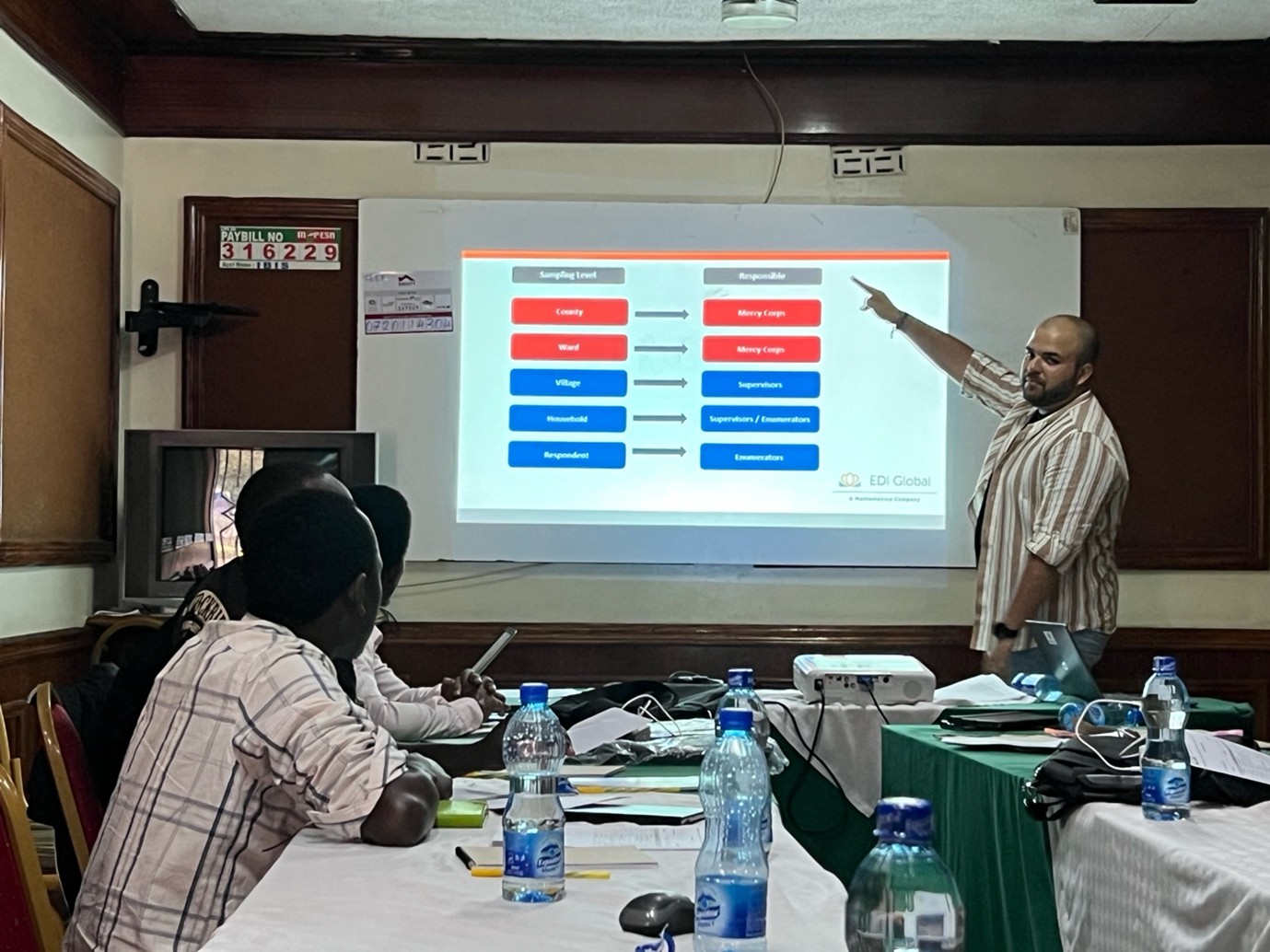

SPARC member organisation Mercy Corps partnered with EDI Global in 2023 to conduct a large-scale survey with 2,856 agropastoralists across five counties in northern Kenya. We wanted to understand how the WDP participatory governance intervention shaped community attitudes and behaviours around local decision-making. To do this, we sampled both WDP and non-WDP wards to enable comparison.

From the initial pilot of the survey tools in one county through to full implementation, adaptive management was essential. The team faced challenges including flooding, roadblocks, limited male respondents, and localised insecurity. These made rigid protocols unworkable. Yet adaptation still had to balance methodological rigour with timeliness and feasibility.

Real-time coordination between research leads and the survey team made this possible. Mercy Corps brought deep contextual knowledge and flexibility, while EDI Global ensured high-quality data was delivered on time and on budget. Together, we adjusted protocols without compromising research integrity.

To illustrate how rigorous data collection and adaptive management worked in practice, here we highlight three brief examples, along with related lessons for future research in fragile contexts affected by climate change.

1. Adjusting sampling to suit the geography of agropastoralist communities

In many surveys in the global south, random walk sampling is used to select respondents cost-effectively. This involves skipping a set number of homes between interviews to ensure a representative sample. But in northern Kenya, this approach quickly ran into trouble.

Our original skip interval was typically between four and seven homes, depending on the number of homes in each community. However, this wasn’t feasible in agropastoralist areas with sparse settlements and difficult terrain. In the pilot, we learned that skipping multiple homes could mean walking 10 kilometres or more between interviews.

EDI Global team members and a local chief on the arduous walk between homes in the survey pilot - Image by Ryan Sheely

During the pilot, we adjusted the skip interval to one, meaning that enumerators left out only one home between interviews. Because the segment of the village was randomly selected, this change preserved the integrity of the sample while making the work manageable.

Having Mercy Corps researchers, EDI Global survey leads, and field teams all present during the pilot made this possible. Seeing the terrain firsthand helped everyone understand the need for adaptation—and agree on a solution.

A supervisor from the Isiolo Field Team said: “At first, we thought the skip pattern would work fine, but once we hit the first village, it was clear that skipping even two households could take us hours. Being able to revise our approach in the field, with everyone aligned, saved the whole operation.”

Key learning: In sparsely populated areas, long skip intervals can make surveys unworkable. Keep intervals short and involve field teams early to test feasibility.

2. Sampling ‘on the move’ for a 50:50 gender sample

One of our key goals was to achieve a 50:50 gender split in each community. We initially assumed that conservative gender norms might make it difficult to reach women and girls. But the pilot revealed the opposite: during the day, agropastoralist communities were not 'raining men' — most were away tending livestock or working. Meanwhile, women were more often at home and accessible.

To meet our gender target, we adapted our random walk sampling protocol. Originally, we planned to interview adults who were in the home. But we revised this to include men we met outside the home on roads, in fields, or near livestock, provided they lived in the sampled community.

This subtle shift made a big difference. Because we had strong default protocols and open communication between field teams, survey leads, and principal investigators, we could make the adjustment quickly and consistently. It was a blend of technical rigour and interpersonal trust that made the adaptation work.

Key learning: In agropastoralist communities, men may be less available during daytime hours. Including mobile respondents—especially those tending livestock—may allow for gender balance.

3. Balancing systems and judgement: pre-emptive planning

Flooding, roadblocks, and localised violence meant some sampled wards were inaccessible. To avoid delays, we needed a plan to replace these wards quickly and credibly.

Before fieldwork began, the research team used the same sampling criteria to pre-identify a list of replacement wards. This meant that whenever the EDI Global field team encountered an access issue, Mercy Corps could immediately suggest a viable ‘next best’ alternative based on the sampling criteria.

Despite working across time zones (East Africa for EDI Global and the United States for Mercy Corps) our teams stayed in sync through WhatsApp and regular check-ins. The trust built during survey preparation, combined with a shared commitment to learning and flexibility, made it possible to adapt without compromising quality.

“There were days when we had to reroute entirely because of flooding or security alerts. But the backup plans were already in place, and communication with EDI Global and Mercy Corps was constant. That’s what made the impossible feel manageable,” said a supervisor from the Garissa field team.

Key learning: In fragile contexts, assume that some areas will be inaccessible. Build a replacement protocol in advance and establish clear, fast communication channels to keep fieldwork on track.

These examples show that adaptive management in survey research relies on more than technical skill. It requires strong relationships, open communication, and a shared willingness to learn and adapt in real time.

In fragile, remote contexts, this collaboration and trust aren't luxuries, they are vital. As the development sector faces growing pressure to deliver in complex environments with fewer resources, we need evidence that balances rigour and flexibility. The WDP survey shows that with the right partnerships and mindset, we can meet that challenge.