Impacts of disruptions to livestock marketing in Sudan

This paper draws on interviews with traders and herders in Sudan, and secondary literature, to gain insight into how the suspended Hajj in 2020 affected livestock traders and herders on low incomes.

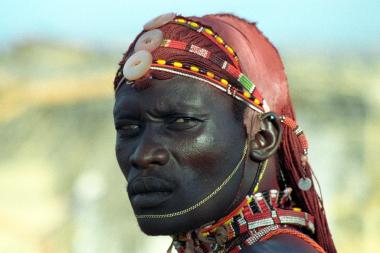

Pastoralists in Sudan rear large numbers of camels, cattle, sheep and goats. The country exports large numbers of live animals - mainly sheep to Saudi Arabia and camels to Egypt. It also exports chilled and frozen meat, mainly to Saudi Arabia, the Gulf States, and Egypt.

Exports of sheep and meat have multiplied by three or more times since 2000, in a trade that - despite looking informal and low-tech - is worth more than US$400 million a year. It is also a trade that provides income for many herders, including people on low incomes.

The marketing chain is well adapted to pastoralism. Livestock marketing has improved gradually over time, through improved infrastructure and services. For example, asphalted roads and the provision of animal quarantine and vaccination facilities.

Yet, the chain has been heavily disrupted. Herders and traders with few alternatives to selling and trading livestock faced heavy losses during the Rift Valley Fever (RVF) outbreaks of 2007 and 2019 that led to export bans of animals and meat. The Covid pandemic of 2020 with its associated partial suspension of the Hajj in Saudi Arabia, and the resulting collapse in export demand, also hit pastoralists hard.

However, once export bans were lifted, marketing has restored to previous levels, and grown larger. While the export of live animals from Sudan is a growing and profitable business, the risks and disruptions traders and herders face remain large.

This paper draws on interviews with traders and herders across Sudan about their responses to the suspended Hajj. It recommends that policy-makers and those working with livestock herders and traders must explore ways to reduce the occurrence of major shocks, and their severity and costs:

The Government of Sudan is aware of the threat that RVF poses. Traders realise the importance of vaccinating and quarantining animals for export. However, additional veterinary health measures against further outbreaks of RVF may be valuable;

Some shocks may be unforeseeable and unavoidable. Policy-makers, traders and herders can consider whether some form of insurance or mutual assistance fund is feasible and desirable. For example, a small annual premium paid in return for a guaranteed monthly payment during specified incidences of shocks;

Sudanese traders exporting live animals may be vulnerable to price setting by importing countries. This raises the issue of whether slaughtering animals in Sudan then sending chilled or frozen meat might be a better option. However, the economics of this remain to be established. This is also not an option for the millions of sheep sent for the Hajj, when sacrifice demands a live animal.